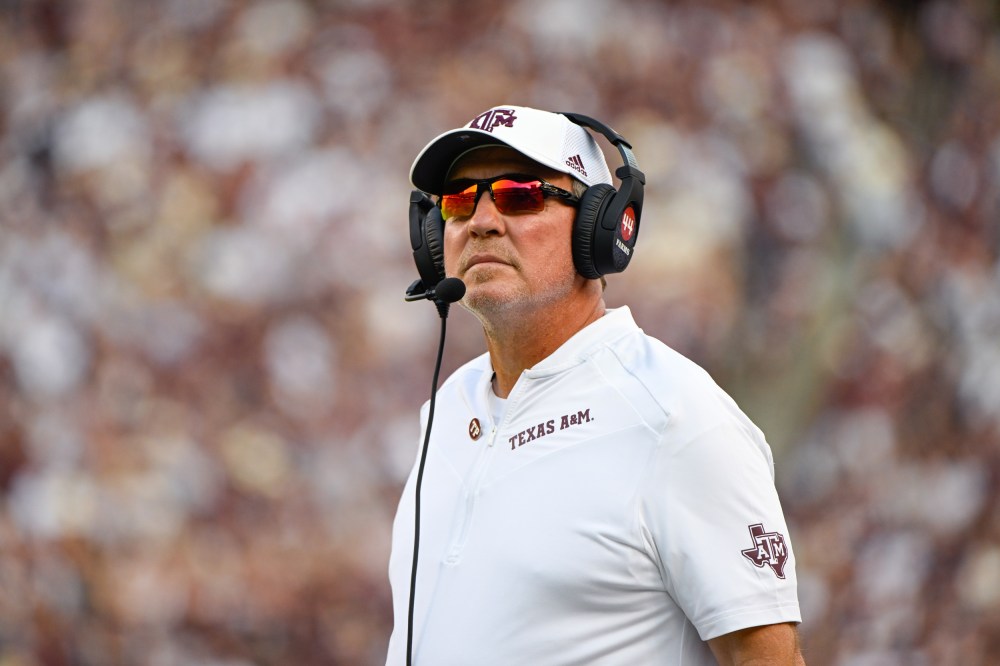

I recently found myself trying to explain to a French academic why an American head football coach at a state’s flagship university is typically the highest-paid public employee in that state. He understood English fine, but my words made little sense to someone from a country where universities don’t fund semiprofessional athletic programs. But even more outrageous than the amount college coaches get paid to man the sidelines of the gridiron is the amount they get paid to go away.

Even more outrageous than the amount college coaches get paid to man the sidelines of the gridiron is the amount they get paid to go away.

Texas A&M fired head coach Jimbo Fisher last weekend, but because of the terms Fisher had negotiated in his contract, the school is now on the hook to pay him $77 million, which The Associated Press says is “the highest paid to a coach in college sports history.” Other failed-and-fired football coaches have similarly benefited from massive buyouts. Mississippi State could owe first-year coach Zach Arnett up to $4.5 million after it fired him this week. The University of Texas knew it would owe Tom Herman as much as $15.4 million when it fired him in 2021. To let football coach Will Muschamp go in 2020, South Carolina was willing to shell out $12.9 million, and Auburn was on the hook for up to $21.5 million to coach Gus Malzahn when it fired him that same year.

We don’t have to wait until a coach is fired to know how much he’ll get if he’s fired. Lucrative buyout clauses are typically negotiated before coaches even agree to come. The University of Georgia, whose Bulldogs are the reigning national champions, could owe Kirby Smart $92.5 million if it fired him now. James Franklin at Penn State would be owed up to $64.5 million. Dabo Sweeney, who coaches at Clemson, would be owed up to $64 million. The list goes on. In its story, the AP lists the current buyout amounts for 10 active college football head coaches.

Those buyout amounts are often offset by money fired coaches make in their next coaching position, but, per the terms of Fisher’s contract, Texas A&M will owe him the full $77 million even if he gets hired somewhere else.

As a professor at Louisiana State University, a large school in the Southeastern Conference, I’m often as baffled as anyone about why universities such as mine prioritize athletics over academics. Here at LSU, several presidents and most of the faculty have long yearned to replace our decrepit, leaking and crumbling 65-year-old library. The price tag is roughly $150 million. It’s a substantial amount, and after having tried for years, the school couldn’t find anyone to contribute that money. And the state has, so far, not funded the project.

But over the past two years alone, LSU quickly raised a new library’s worth of funds from private donors for the school’s true priorities: football, basketball and baseball. When LSU needed to guarantee head football coach Brian Kelly’s 10-year, $95 million contract in 2021, it quickly raised the money. When the women’s basketball team won a national championship this year, LSU quickly renegotiated coach Kim Mulkey’s contract and found $36 million to pay her over 10 years. And the school promptly found $12.5 million to give baseball coach Jay Johnson a new seven-year deal after his team won the 2023 College World Series. All that money, $143.5 million, is nearly enough for a palatial new library.

LSU owed Ed Orgeron, the coach of the team’s national championship-winning 2019 football team, $16.9 million after it fired him in 2021. Some people in Baton Rouge considered that obscene. But then, LSU hired Kelly and would have to pay him up to $70 million if it lets him go now.

Kelly apparently left Notre Dame for LSU because he believed LSU wouldn’t waste precious resources on academic buildings. “I loved my time at Notre Dame,” Kelly told ESPN in September. “I have nothing but great memories there. But the whole landscape there is different than it is here. It just is. There are priorities at Notre Dame. The architectural building needed to get built first.” Then, referring to LSU, he said: “They ain’t building the architectural building here first. We’re building the athletic training facility first.” To his point, in 2019, two years before Kelly arrived, LSU spent $28 million on an extravagant new locker room for football players.

LSU paid Ed Orgeron, the coach of the team’s national championship-winning 2019 football team, $16.9 million after it fired him in 2021. Some people in Baton Rouge considered that obscene. But then, LSU hired Brian Kelly and would have to pay him up to $70 million if it lets him go now.

Kelly quickly tried to walk back those remarks, telling a local news outlet, “My comments was that there was a priority placed on excellence, excellence both in academics and athletics. That’s what drew me to this job.” And LSU President William Tate defended the university’s priorities, noting the state has made significant infrastructure investments at LSU in recent years. “We remain steadfast in our dedication to supporting our academic and research endeavors,” he said.

So said the university president who is paid less than 10% of what the football coach makes yearly.

Whenever anyone calls football coach buyouts what they are, a government welfare program for failed coaches, the schools’ boosters invariably howl that it’s all private money and nobody’s concern but the athletic departments’. “How much revenue did you generate for your school last year?” I’m asked when I condemn the embarrassing disparity between faculty and coach compensation. In other words, “The whole thing is strictly business; you stick to teaching.”