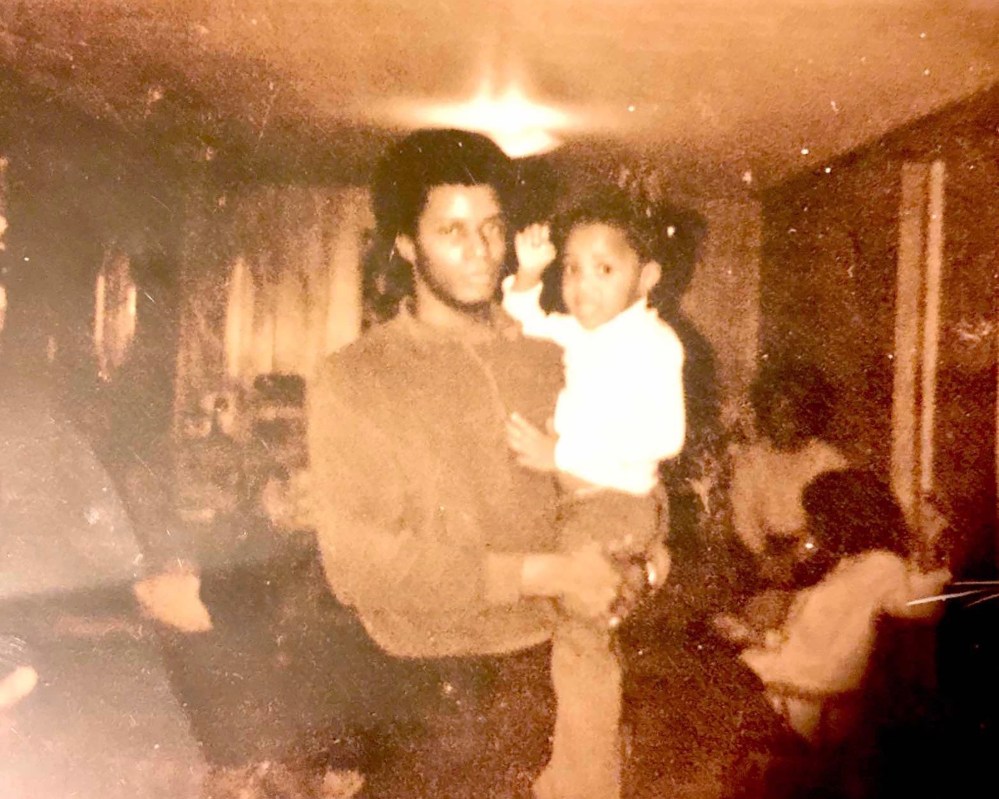

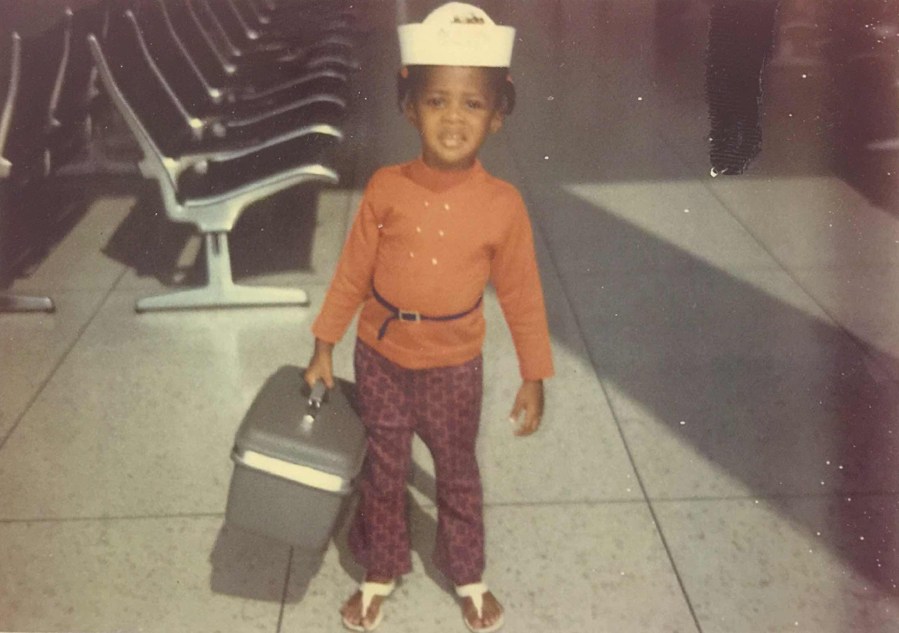

I am not supposed to be here. Born a 6-pound, 7-ounce Black girl in 1967 at Crosby Memorial Hospital in Picayune, Mississippi, the odds were stacked against me from the beginning. Mississippi had one of the highest infant mortality rates in the nation at 35.3 deaths per 1,000 live births that year. And the rate that year for nonwhite infants like me was 47.4 per 1,000 live births. A small fraction of Black people born a generation or so ahead of me made it to the end of high school. Based on when and where I was born, my current success is something of a miracle.

What made the difference in my life? Early Head Start, which President Lyndon B. Johnson launched in 1965.

What made the difference in my life? Early Head Start, which President Lyndon B. Johnson launched in 1965 as part of his “War on Poverty.” In my case, Head Start wasn’t just an educational program, but a lifeline. It operated out of the church annex of the Pilgrim Bound Baptist Church in Picayune, where three generations of my family had been active members. At that Head Start, my great aunts and my grandmother helped create a haven where genuine learning flourished and where we received hot meals each day.

That’s why it’s so distressing to hear news of the current administration’s plan to eliminate funding for Head Start, yet another goal of Project 2025.

I still vividly remember the arts and crafts projects we created at Head Start, the plays we performed and, most importantly, how learning was made fun and engaging. Head Start was one of the biggest influences on my growth and development. It was indeed one of the few times in my early life where I felt truly loved, seen and supported in a place of learning.

Most significantly, this nurturing environment became the pathway for my development as an artist and creator. In that church annex, creativity had no boundaries — we were encouraged to express ourselves through art, storytelling and performance. The teachers never limited our imagination but instead fostered it, showing us that possibilities were limitless. They seamlessly wove together community, learning and creativity in ways that showed me from the earliest age that these elements weren’t separate but deeply interconnected.

My subsequent educational journey unfolded quite differently. The public schools for Black students in the late 1960s and early ’70s remained deeply underfunded and segregated despite supposed progress. Academic research shows the magnitude of these educational disparities in Mississippi: Of the 1,286,272 Black students who began first grade from 1941 to 1958, only 10.4% persisted to 12th grade, and more than 730,000 left school after just the first grade.

I was fortunate; Head Start was the reason I could read and write at an early age. According to my mother, I had “a solid command of the English language,” probably because I was “around a bunch of old women.”

Many of my peers weren’t as fortunate. They hadn’t been given the same solid foundation that Head Start gave me, and the difference was apparent.

Many people fail to understand that Head Start isn’t just an educational program; it’s a comprehensive approach to child development that addresses emotional, social, health and nutritional needs alongside academic preparation. For a Black girl in Mississippi in the late 1960s, these supports weren’t just helpful —they were essential.

And they remain so. Yasmina Vinci, executive director of the National Head Start Association, told USA Today that eliminating Head Start’s budget would end meals, health care and developmental screenings for 800,000 children and leave their parents unable to work.