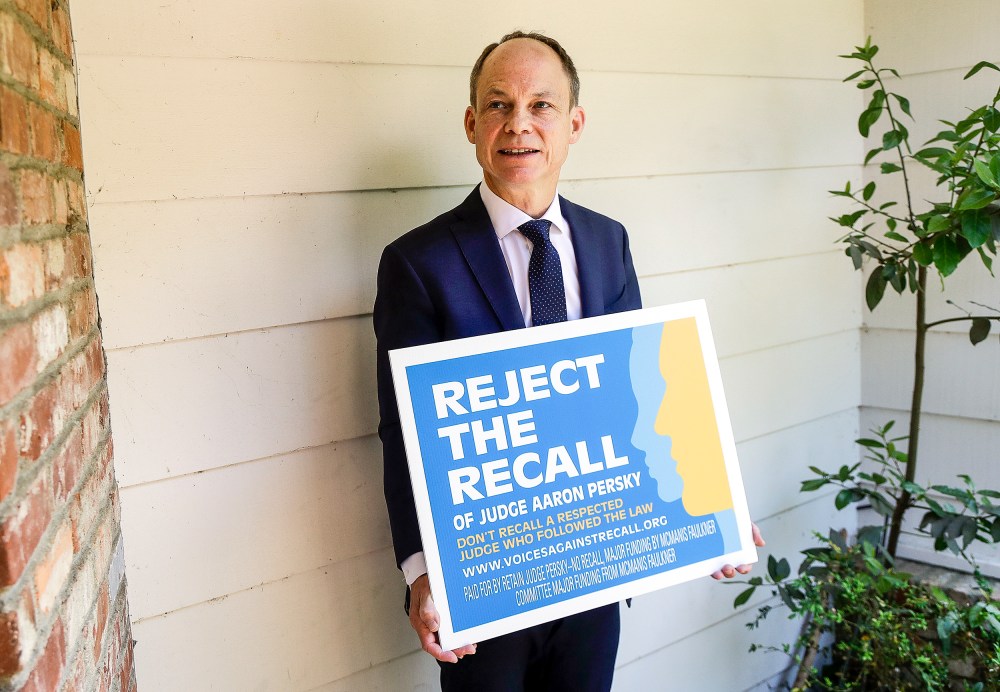

“The Stanford sexual assault case: a white privilege cake with vanilla frosting on top” proclaimed a Guardian headline following the public backlash to the Brock Turner sentence and the campaign to remove the judge who delivered it. The subsequent recall campaign condemned Judge Aaron Perksy as the very symbol of state-sanctioned white privilege and male entitlement that needed to be taken down.

And it was effective. On May 18, 2018, Persky became the first judge to be recalled in California in 80 years. But was this really progress for criminal justice?

The subsequent recall campaign condemned Judge Aaron Perksy as the very symbol of state-sanctioned white privilege.

Even at the time of the recall campaign, there was a small chorus of people who saw the recall not as a victory for women and a symbolic triumph over white privilege but as a deeply misguided effort that did little for survivors and exacerbated the over-incarceration of Black people and other marginalized groups. And indeed, Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons at up to five times the rate of white Americans.

These critics were not rape apologists. They were women and people of color, and some were, like me, sexual assault survivors. They were people with intimate knowledge of our criminal justice system who had repeatedly seen popular outrage lead to punitive state responses that made the U.S. the country with the highest rates of incarceration in the world.

And such concerns, it turns out, were well founded. A peer reviewed study validates what opponents feared would happen — in the wake of the recall, California judges became far more punitive in sentencing, and not just for sex offenses and privileged defendants. According to study authors Sanford C. Gordon and Sidak Yntiso, in the six weeks following the announcement of the campaign to recall Judge Persky there was a 30% increase in sentences across the state. In total, the judges in the six counties studied gave between 88 and 403 years of additional incarceration (as calculated by the authors) in that period. Extrapolating this to all of California, the study found that recall-related prison time could be as much as 2,442 years. Because of entrenched racial disparities in criminal law administration, communities of color disproportionately shouldered this burden.

The study echoes what many who engage in racial justice and anti-incarceration work already know: A punitive response to injustice that calls for harsher sentences, even when aimed at the privileged, inevitably harms the people against whom the system is already stacked.

The newly released documentary short “The Recall Reframed” explores the tensions that arise when a social-justice movement like feminism equates long prison sentences with justice and uses progressive rhetoric to achieve regressive ends. How can we respond to injustices without bolstering a criminal system that throughout history has caused grave injustices and oppressed many people? Do knee-jerk punitive impulses like those at play in the recall effort serve any goal other than satisfying popular outrage, or are they simply, as James Baldwin wrote, the “habits of thought [that] reinforce and sustain the habits of power”?

What we have here is a failure of imagination. Too many people could not imagine it possible to condemn the profound harms of sexual violence without doubling down on an overly broad and overly harsh criminal justice system that often fails to help survivors but succeeds in perpetuating racial, social and economic inequality.