In 2023, Taylor Swift achieved total pop music ubiquity. Her Eras Tour became the highest-grossing tour of all time. She was named Time’s Person of the Year. She won album of the year at the Grammys. She became a billionaire. And her whirlwind romance with Kansas City football star Travis Kelce launched a hundred Fox News conspiracy theories.

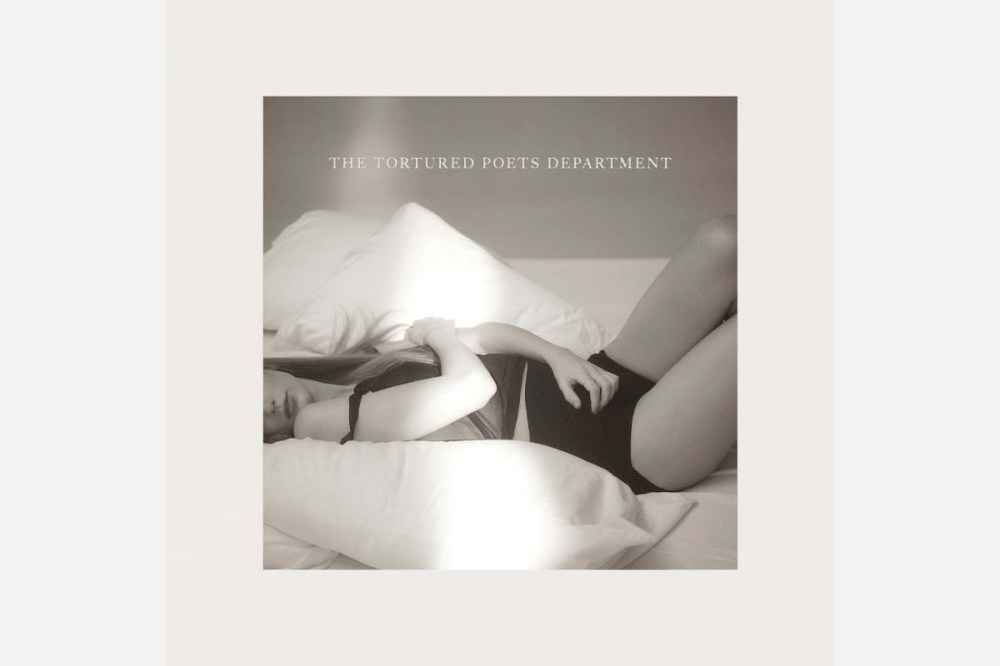

Amid this chaos and success, on Friday Swift released her 6th project in three years, “The Tortured Poets Department.” On one hand, the project is proof of her business acumen: iHeartRadio rebranded Friday “iHeartTaylor” and streamed the entire album as soon as it came out; Instagram designed a new feature specifically for her to tease the project. But Swift positions the album as an emotional salve. These were songs she “needed to make … more than any of my albums that I ever made.” Finished on tour amid the end of a six-year-relationship, there was certainly plenty for her to parse. But the first half of the (surprise double) album especially is too lyrically broad to feel especially poignant. Swift’s most intense feelings come across when she talks about her career and the scrutiny she faces as a public figure. But ultimately “The Tortured Poets Department” feels like a portrait of heartbreak that often avoids the details of what made the love so special and the separation so painful, and a criticism of celebrity that feels as much a product as it is a musical offering.

“The Tortured Poets Department” feels like a portrait of heartbreak that often avoids the details of what made the love so special and the separation so painful.

The synth-pop arrangements on the original 17 songs sound a lot like “Midnights,” and as a result are too often homogenous. Choruses tend to echo and drift rather than build, and a general glossy smoothness tamps down Swift’s vocals. Lyrically, Swift skirts the confessionalism or candor that might give these songs emotional urgency. On “Down Bad,” she reveals, “For a moment I knew cosmic love,” only to follow it up with “Now I’m down bad crying at the gym.” On “Alchemy” she begins, “This happens once every few lifetimes” before saying “These chemicals hit me like white wine.” These are references that feel engineered for widespread appeal rather than personalized storytelling.

At her best, Swift is a master of synecdoche. She outlines a narrative full of tension, misunderstanding, or regret and then fills in the gaps with tiny memories that evoke entire worlds outside the frame. But here again, the first half of “Tortured Poets” underwhelms, as that framing largely slips away. There are very few stories, and more statements of feeling. The random details she provides serve little purpose. Her mention of Charlie Puth (“You smokеd, then ate seven bars of chocolate/ We declared Charlie Puth should be a bigger artist”) on the title track tells us nothing about her and an ex’s dynamic except that they shared surprisingly bad music tastes. The same song uses the device of a typewriter to point to an ex’s pretentious taste, but tells us nothing about how that character trait made her feel or how it impacted their dynamic.

On earlier albums, Swift released her worst songs as singles as a kind of red herring for the tone of the album. (“ME!” was a single on the album that had “Cruel Summer,” for example.) With “Midnights” and “The Tortured Poets Department” she does this but on a bigger scale, following both pop albums with more introspective, delicate, acoustic tracks released a few hours later. These songs, mostly produced by Aaron Dessner and written in Swift’s “quill pen” literary prose style, are infinitely more textured, imaginative, and intriguing. On “So High School,” Swift’s gauzy falsetto meshes beautifully with a gnashing ‘90s guitar line, seamlessly relaying a nostalgic sense of euphoria. On gentle piano ballad “Robin,” Swift observes a child’s sense of innocence with care and poignant yearning. And the finger plucked guitar on “I Look In People’s Windows” beautifully expresses a sense of hope that a glimpse of a lost love can spark.

These songs engage in the world-building and storytelling that is Swift’s forte. But they still never quite reach the self-interrogation, empathy, or wisdom of “folklore” and “evermore,” which are the most stylistically similar releases in her catalog. There is a lingering sense of remove here; ornate language papering over a lack of intimacy and complexity.