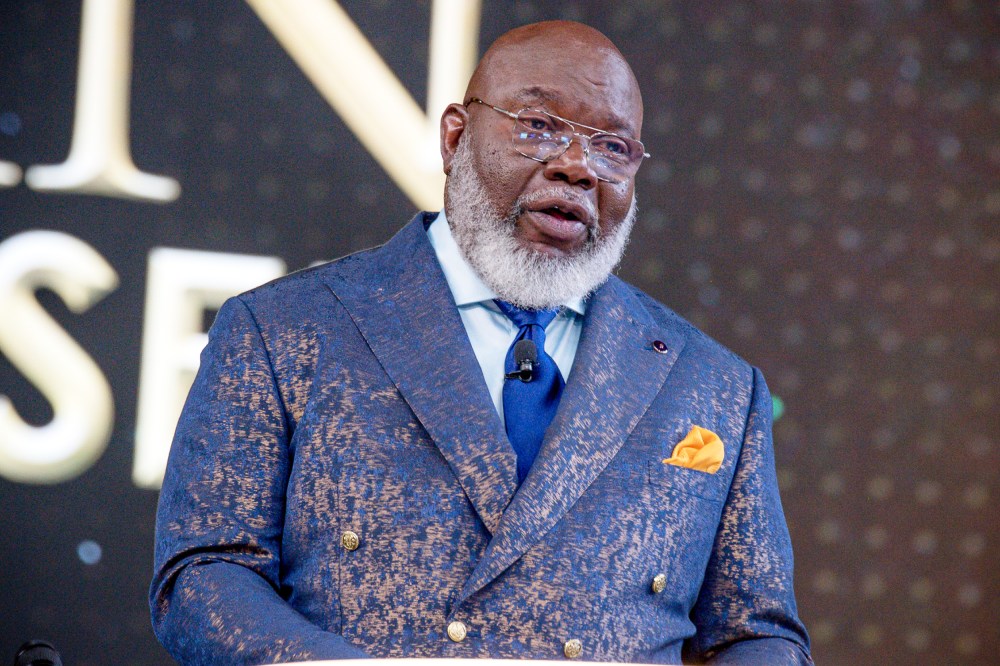

Bishop T.D. Jakes, arguably the most well-known Black religious leader in the United States and whose Dallas church, The Potter’s House, ranks among the country’s largest congregations, has announced a new 10-year deal between T.D. Jakes Group and Wells Fargo to build mixed-income communities in underserved neighborhoods. Even though the partnership is not with his church, Jakes is still best known as a pastor, and in working with a financial institution that’s been repeatedly accused of racist lending practices, Jakes will likely be hurting a Black community he says he wants to help. Indeed, his partnership with Wells Fargo is tantamount to his working with the fox to raid the henhouse.

In working with a financial institution that’s been repeatedly accused of racist lending practices, Jakes will likely be hurting a Black community he says he wants to help.

For almost 20 years, Wells Fargo has had an abysmal record in the African American community regarding mortgages and loans. According to federal prosecutors, starting four years before the 2008 financial crisis that caused the Great Recession, Wells Fargo, the fourth largest bank in the U.S., “discriminated by steering approximately 4,000 African-American and Hispanic wholesale borrowers, as well as additional retail borrowers, into subprime mortgages when non-Hispanic white borrowers with similar credit profiles received prime loans.” Baltimore city officials complained at that time that Wells Fargo’s policies had pushed hundreds of borrowers in that city into foreclosure.

Four years later, in 2012, Wells Fargo was ordered by the Justice Department to pay $175 million to settle allegations that it discriminated against African American and Hispanic borrowers between 2004 and 2009. Wells Fargo denied that it had actually discriminated and said in a statement that “Wells Fargo is settling this matter solely for the purpose of avoiding contested litigation with the DOJ.” The $175 million included $125 million to borrowers who were discriminated against and $50 million “in direct down payment assistance to borrowers in communities around the country where the department identified large numbers of discrimination victims and which were hard hit by the housing crisis.”

In 2018, the National Black Church Initiative, a coalition of 150,000 African American and Latino churches that fights racial disparities, announced a nationwide boycott of Wells Fargo because of that history of pushing subprime loans on Black people. But complaints against the bank didn’t end. In a class-action lawsuit filed in California in April 2022, Wells Fargo was once again accused of racist lending. According to plaintiffs in that class-action lawsuit, Black loan applicants with high credit scores were given interest rates that were higher than white loan applicants with high credit scores.

In denying those claims, Wells Fargo said in a statement, “We are deeply disturbed by allegations of discrimination that we believe do not stand up to scrutiny … These unfounded attacks on Wells Fargo stand in stark contrast to the company’s significant and long-term commitment to closing the minority homeownership gap.”

In March, a federal judge in Ohio held off approving a $94 million settlement between Wells Fargo and borrowers who claimed the bank wrongly sent their mortgages into forbearance because, he wrote, the class-action lawsuit in California needs to be resolved first.

In 2018, the National Black Church Initiative, a coalition of 150,000 African American and Latino churches, announced a nationwide boycott of Wells Fargo.

In a separate set of complaints that don’t allege racism, in January, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announced that Wells Fargo broke “federal consumer laws that apply to financial products, including auto loans, mortgages, and bank accounts” and that it would be paying “$2 billion to customers who were harmed, plus a $1.7 billion fine that goes to the victims’ relief fund.”

That’s still not all. In May 2022, The New York Times quoted seven people who had worked or still were working for Wells Fargo who said they’d been instructed to give sham interviews to so-called “diverse” candidates after the company had already decided to hire someone else. And some shareholders have filed suit against Wells Fargo claiming that the sham interview policy had hurt the company’s reputation and stock value. In a written statement to Bloomberg Law, a spokesperson said, Wells Fargo “is deeply committed to diversity, equity and inclusion. We disagree with the claims, and look forward to defending ourselves against them.”

Despite what the company says in its statements about its commitment to fair hiring practices and fair lending practices, there appears to be a pattern with Wells Fargo, one that the National Black Church Initiative thought was troubling enough to call for a boycott. Why, then, is Jakes partnering with a lender that has an abysmal record in the communities he says he wants to serve?

In an April 27 appearance on CBS Mornings, where he announced the partnership, Jakes was asked about the “illegal overdraft fees, illegal fees tied to car loans, illegal fees tied to mortgages” that led to the $3.7 billion settlement with the CFPB. He said those bad practices were “exactly the reservations that I had with them as well. Initially, several years ago, when they talked to me, I would not do business with them for those very reasons.”

Jakes said, “That settlement that came out came from the previous administration. They have a new leader now. They have a new administration and they’re beginning to right some of the wrongs.” He said, “Wells Fargo stood up and said, you know, I’m willing to make this unlikely alliance, this very unique alliance.” Then Jakes called attention to his book “Disruptive Thinking” and said that “this disruptive alliance between us is designed to lift up underserved and underrepresented communities.”