It’s hard to think of a famous Supreme Court plaintiff with whom former President Donald Trump has less in common than Lee Yick, a Chinese immigrant who was convicted of operating an unlicensed laundry in late-19th-century San Francisco. Yick sued, arguing that San Francisco’s pattern of denying permits to virtually every Chinese applicant while granting them to virtually every white applicant violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court’s 1886 decision in his case, Yick Wo v. Hopkins, still stands today. It says that the application of a race-neutral law, such as San Francisco’s laundry-permitting scheme, can be so obviously discriminatory that it demonstrates an intentional (and actionable) violation of the Constitution.

It’s hard to think of a famous Supreme Court plaintiff with whom former President Donald Trump has less in common than Lee Yick.

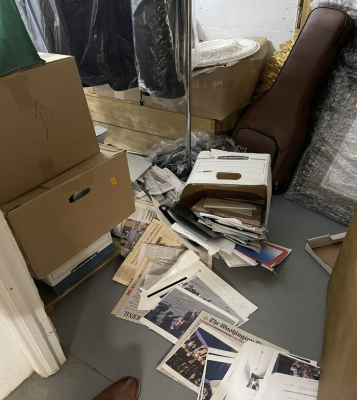

Donald Trump is no Lee Yick. And yet, in a motion filed Thursday in Florida, his lawyers argue that Yick’s case provides a precedent for throwing out the charges in the Mar-a-Lago classified documents prosecution. They say federal prosecutors are engaged in unconstitutional “selective prosecution” of Trump. There are two different, but equally fatal, problems with Trump’s argument. First, for better or worse, the Supreme Court has made selective prosecution claims notoriously difficult to prove. Second, Trump is just about the worst possible person to bring a selective prosecution claim — since so much of his allegedly unlawful conduct in the Mar-a-Lago case is unprecedented.

A claim for selective prosecution is, in essence, a claim that the government chose to prosecute a defendant for the exact same conduct for which it chose not to prosecute a different individual. The claim includes the argument that there was no good reason (and, indeed, a nefarious one, like race or political views) for treating the two cases differently. The argument is not that the defendant is innocent; it’s that the government’s misconduct in singling out the defendant ought to be punished — by barring the prosecution of even a guilty defendant.

Perhaps because the stakes are so high, the Supreme Court in recent decades has made selective prosecution claims much more difficult to prove. Under a series of cases in the late 1990s, for instance, the justices regularly held that to establish a selective prosecution claim, the burden is on the defendant to identify materially similar cases that the government did not prosecute. And even then the selective prosecution claim would fail if the government had a good reason for not having brought the other case: Say, a suspect in that case cooperated with law enforcement or there were evidentiary issues.

Only if the defendant could prove that the government had deliberately and intentionally singled him out from other similarly situated suspects without any good reason would such a claim succeed. This is why, for instance, it is exceedingly difficult to prove racial profiling claims. To establish that a police officer only gives speeding tickets to Black motorists, for example, a plaintiff would have to provide evidence of the officer not pulling over other non-Black motorists engaged in the same behavior. The plaintiff would have to prove a negative.